In the world of chemistry, stereoisomerism is a concept that reveals the subtle complexities and brilliant diversity within molecules. Among the fascinating classes of stereoisomers are diastereomers—molecules that share the same molecular formula and connectivity but differ in the spatial arrangement of their atoms. Diastereomers play crucial roles in organic chemistry, pharmaceuticals, and biology, making them a cornerstone topic for students, researchers, and professionals alike.

This article offers an in-depth exploration of diastereomers: what they are, how they differ from other isomers, why they matter, and how scientists identify and utilize them in science and industry.

What Are Diastereomers?

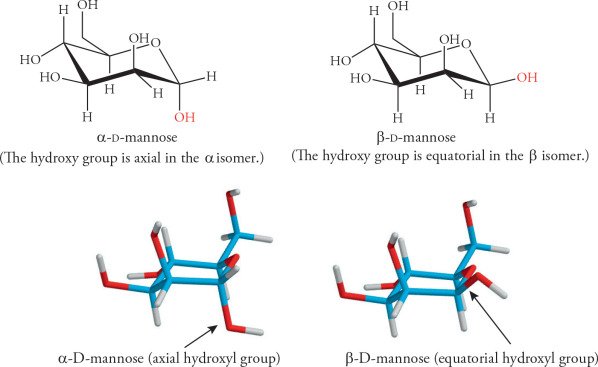

Diastereomers are a type of stereoisomer. Stereoisomers are compounds that have the same molecular formula and sequence of bonded atoms (constitution), but their atoms are arranged differently in space. Diastereomers are defined as stereoisomers that are not mirror images of each other.

To better understand this, let’s look at stereoisomerism’s two major categories:

- Enantiomers: Stereoisomers that are non-superimposable mirror images of each other (like left and right hands).

- Diastereomers: Stereoisomers that are not mirror images and not superimposable.

In most cases, diastereomers arise when a molecule has two or more chiral centers (stereocenters)—atoms, typically carbons, with four different groups attached.

Key Characteristics of Diastereomers

- Not Mirror Images: Unlike enantiomers, diastereomers do not relate to each other as mirror images.

- Different Physical Properties: Diastereomers often have different melting points, boiling points, solubilities, densities, and refractive indices, making them easier to separate than enantiomers.

- Different Chemical Properties: They can react with chemical reagents at different rates and sometimes even give different products.

- Optical Activity: While enantiomers rotate plane-polarized light to the same degree but in opposite directions, diastereomers may differ in both the degree and direction of optical rotation—or one may not rotate light at all.

Diastereomers vs. Enantiomers: The Crucial Distinction

Understanding the difference between diastereomers and enantiomers is vital:

- Enantiomers always come in pairs and are exact mirror images.

- Diastereomers may be more than two, depending on the number of stereocenters, and are not mirror images of each other.

For example, a molecule with two chiral centers can have up to four stereoisomers: two pairs of enantiomers, each non-mirror-image pair being diastereomers.

Examples of Diastereomers

1. Tartaric Acid

Tartaric acid (a dicarboxylic acid) is a classic example. It has two chiral centers and three stereoisomers:

- (R,R)-tartaric acid

- (S,S)-tartaric acid (enantiomer of R,R)

- (R,S)-tartaric acid (a meso compound, achiral but with chiral centers)

(R,R) and (S,S) are enantiomers. Each of these is a diastereomer to the (R,S) meso form.

2. 2,3-Butanediol

This molecule has two chiral centers:

- (2R,3R)-butanediol and (2S,3S)-butanediol: enantiomers

- (2R,3S)-butanediol: diastereomer to both above

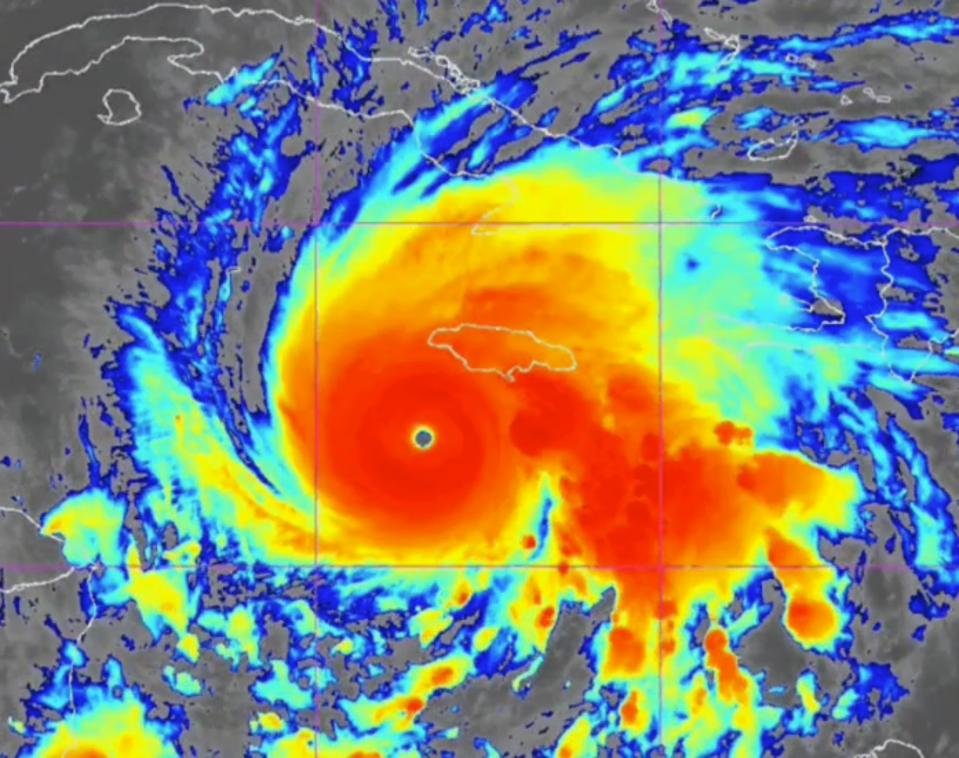

3. Glucose and Galactose

These two sugars are both aldohexoses and differ in the configuration at one stereocenter (the fourth carbon), making them diastereomers. This subtle difference is the reason for their distinct biological roles and properties.

The Importance of Diastereomers in Nature and Industry

1. Pharmaceuticals

Diastereomerism is highly significant in drug development. Diastereomers can have vastly different pharmacological effects—one may be therapeutic while another could be inactive or even harmful. Chemists strive to isolate and study each diastereomer separately.

Example:

Thalidomide exists as two diastereomers; one has therapeutic effects, while the other causes severe birth defects. This infamous case underscores the necessity of stereochemical awareness in drug design.

2. Biological Recognition

Many biological molecules, such as amino acids, sugars, and nucleic acids, are chiral and can exist as different diastereomers. Enzymes and receptors are stereospecific; they may recognize and interact with only one diastereomer, dictating the course of metabolic pathways.

3. Materials Science

Diastereomers can have different physical behaviors that are exploited in the design of new materials, such as liquid crystals and polymers with specific properties.

Identification and Separation of Diastereomers

1. Physical Methods

Because diastereomers have differing physical properties, they can often be separated by:

- Crystallization: Exploiting differences in solubility.

- Distillation: Using different boiling points.

- Chromatography: Especially high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or gas chromatography (GC).

2. Spectroscopic Techniques

- NMR Spectroscopy: Diastereomers often show different chemical shifts and coupling patterns.

- Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy: Differences may be subtle but can exist, especially in functional group regions.

- Optical Rotation: Measurement of the angle of rotation of plane-polarized light, though this is more diagnostic for enantiomers.

3. Chemical Methods

- Chiral Derivatizing Agents: These can convert enantiomers into diastereomers, which are then more easily separated and analyzed.

Stereochemistry and the Number of Diastereomers

For a molecule with n chiral centers (and no symmetry), the maximum number of stereoisomers is 2ⁿ. Of these, half are enantiomers, and the rest are diastereomers. However, the presence of symmetry (as with meso compounds) can reduce the actual number.

Real-World Applications and Case Studies

1. Carbohydrates

Monosaccharides like glucose, galactose, and mannose are all diastereomers. The body’s enzymes are tailored to recognize only specific diastereomeric forms—a fact vital to metabolism and nutrition.

2. Agrochemicals

Many pesticides and herbicides are chiral. Diastereomers may differ in their environmental impact and effectiveness, leading to regulatory focus on their synthesis and separation.

3. Food Chemistry

The flavor and aroma of foods can depend on the specific diastereomer present. For instance, the diastereomers of limonene smell like lemons or oranges, respectively.

Challenges and Future Directions

The synthesis, identification, and purification of diastereomers remain active areas of research. Advances in chiral catalysts, analytical techniques, and computational chemistry are enabling more efficient production and characterization of specific diastereomers, which is crucial for pharmaceuticals, materials, and biotechnology.

Conclusion

Diastereomers are more than a textbook concept; they are central to the molecular diversity that underpins modern chemistry, biology, and industry. Understanding diastereomers—how they differ from enantiomers, their properties, and their profound effects on reactivity and biological function—empowers chemists to design better drugs, materials, and processes. As scientific techniques advance, the ability to harness the unique properties of diastereomers will only grow, paving the way for new discoveries and innovations in science and technology.